When the U.S. installed a Confederate officer in charge of its new Philippine territory

On Feb. 1, 1904, America changed its tone on its new oriental territory. To hell with democratization. The new policy: tax and subjugate Filipinos to benefit the U.S. and its military.

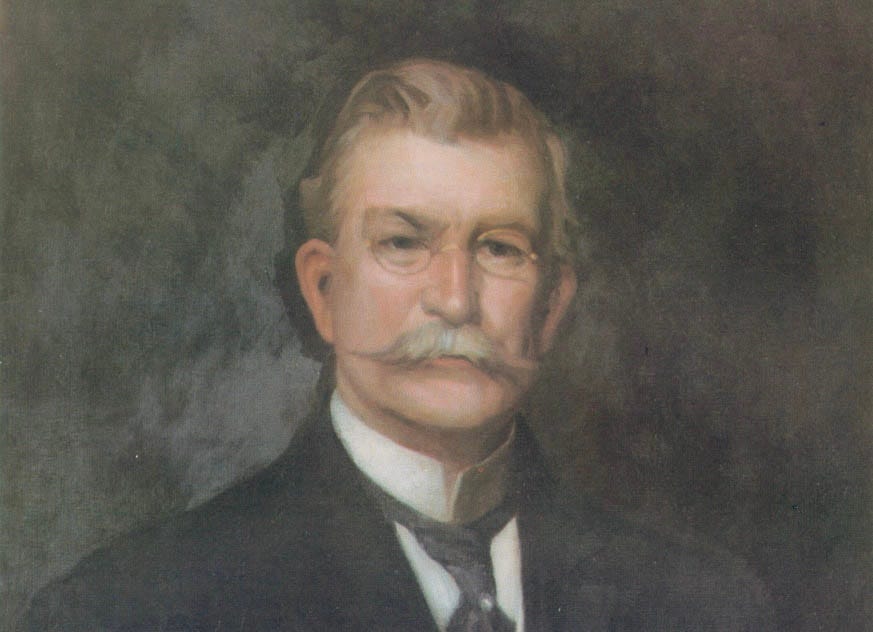

Luke Edward Wright. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

For me, this history is not just a collection of dates and titles; it is the story of my own family’s survival. While Luke Edward Wright was busy reorganizing the islands to fit his vision of order, my great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents were living through the daily reality of his “firm hand.” They felt the weight of the taxes he imposed and the chilling presence of the Constabulary in their communities.

Eventually, my great-grandfather sought a different future, leaving the archipelago for the Territory of Hawaii. He arrived to labor in the sugarcane fields, a grueling path that many Filipinos took to escape the stifling colonial atmosphere at home. He chose to settle our family there, trading one island territory for another, but carrying the resilience forged under Wright’s administration with him.

On Feb. 1, 1904, Wright stepped into the sweltering heat of Manila to take command of the Philippines. He was a former Confederate officer, a man whose worldview was shaped by the rigid racial hierarchies of the American South.

When he became governor-general, the change was more than just a new title. It was a calculated move that showed the U.S. intended to stay. This new title carried the weight of a permanent empire, suggesting that the U.S. was no longer just a temporary teacher of democracy, but the long-term master of what many in Washington called an oriental prize.

William Howard Taft welcomes Luke Edward Wright to the U.S. Territory of the Philippines and escorts him to his new office. Credit: picryl.com. Public domain.

Wright represented a specific type of American expansion. He viewed the Filipino people not as future citizens, but as “colored” subjects to be managed.

His predecessor, William Howard Taft, had at least claimed he wanted the Philippines for the Filipinos, acting like a father figure. Wright dropped that act. Instead, he brought the firm hand of a man who believed white administrators were naturally superior.

Under Wright’s leadership, the social gap between the occupiers and the local people became a chasm. The U.S. presence was no longer about helpful guidance; it was about the cold reality of taking resources and maintaining strict control.

The American attitude toward the islands at this time was one of intense possession. The archipelago was seen as a vital gateway to Asian markets, a prize that required a tight grip.

Wright’s administration reflected the belief that Filipinos were incapable of ruling themselves and needed the discipline of a leader familiar with keeping people in their place.

This era turned the Philippines into a testing ground for empire. Racial theories from the American South were exported across the Pacific and applied to a new population of darker-skinned subjects.

In his first year, Wright moved quickly to enforce this discipline by expanding the Philippine Constabulary. This was not a standard police force; it was a paramilitary group designed to crush any remaining resistance.

He also backed the Internal Revenue Law of 1904. This law overhauled the economy and placed a heavy tax burden on local people to pay for American building projects.

These roads and ports were not built for the Filipino people. Rather, they were to make it easier for the U.S. to move goods, troops, and those paramilitary constables.

Wright dealt with the Filipino elite with a cold, businesslike approach, giving them small amounts of power only if they helped the U.S. extract wealth and maintain authority.

The local reaction to this shift was immediate alarm. Filipino nationalist newspapers, like El Renacimiento, became the main voices of protest, even while facing strict censorship.

These writers realized the title of “governor-general” meant the U.S. was abandoning the idea of winning people over with kindness. They saw Wright as a man who viewed the islands like a plantation, and their articles showed a deep sense of betrayal.

While some papers tried to stay neutral to survive, most of the Filipino media mourned the death of promised reforms. They pointed out how Wright and his family socially excluded Filipinos, replacing the relative warmth of the Taft years with a system of segregation that made it clear who the masters were.

For my own family, this era of “law and order” was the backdrop of their daily struggle. My great-great-grandparents lived through the imposition of these laws, feeling the tightening grip of a government that saw them as subjects rather than equals. It was this atmosphere of permanent colonization that eventually drove my great-grandfather to look toward the horizon.

My great-grandfather left for the Territory of Hawaii to work in the sugarcane fields, joined by thousands of others who sought a life away from the rigid structures Wright helped build. He chose to settle his family there, planting new roots in Hawaiian soil, but the memory of what they left behind in the Philippines remained a part of our heritage.

By the time Wright took his oath, the bloody Philippine-American War had mostly been silenced, but the peace was fragile and kept in place by fear.

His leadership ensured the colonial government worked mainly for American interests. He famously claimed he wanted equal opportunities for everyone, but his actions proved that equality did not include giving Filipinos any real political power.

The change to the title of governor-general was the final word in a sentence that declared the U.S. a global empire. It was an era defined by a former Confederate’s vision of order, where the dream of Filipino independence was pushed aside for a permanent and deeply racialized American rule.